For the uninitiated I’m going to review some background that I believe is generally accepted among experts before I get to the real point, so if you prefer to jump to where I actually tell you what I think it all means, click here. And if you think this post is worth thinking about, don’t forget to follow and share; there’s more to come.

Filter bubbles are so 2011

By now I suppose most of us have heard terms like “filter bubble” and “echo chamber.” A filter bubble is what you get when internet resources like search engines and dynamic page generation algorithms give returns that are likely to reinforce what you already believe. Echo chambers are social environments where one is surrounded by people and organizations likely to do the same.

Both are a problem because both prevent you from being exposed to ideas that might challenge or add to your prior beliefs — and unless you already have the best ideas you could have, they thus tend to narrow your horizons and limit your learning.

But I am worried that filter bubbles are about to get a terrifying upgrade, with consequences that cannot be foreseen. I think it’s urgent we get ahead of the next evolution of technology before it overtakes us.

Under the Hood

A rapidly rising majority of young adults now get their news primarily from social media and other online resources, so this is the future of news. And entertainment, and socializing, for that matter. But there are a number of conflicting imperatives for the folks running the platforms that actually deliver the content, and that has some undesirable consequences.

To start with, the task of combing and collating the billions of pages on the Internet staggers the imagination — it certainly is beyond human capability to manually curate all of this data and get it timely to the people who want it. Therefore, we rely on machines to do the work.

But the task even of parameterizing all this content is beyond the comprehension of even large teams of experts. Perforce, platforms rely heavily on adaptive software (which I’ll imprecisely refer to as “artificial intelligence,” or “AI’ herein). There are very many different kinds of “machine learning” algorithms; newsfeed generators rely heavily on neural networks.

But the nuts and bolts are a bit beside the point I’ll pursue, which is that nobody understands in detail how these things work. If human beings could understand the problem, or produce the solution, they wouldn’t be resorting to AI in the first place. So what they do is produce two or more versions or adjustments to the software algorithm and test it against some metric (especially time-on-site or link “conversion” (click-through) with respect to social media sites, which profit from user engagement); whichever version produces the preferred output is kept, modified in one or more ways, and tested again, and so on.

Eventually, the algorithm is effective — but inscrutable. All we can say is that it has so far produced output consistent with our goals. This makes it harder to steer the system, and incredibly difficult to fix it when it goes off course. It’s a significant enough problem that it has received the attention of DARPA.

And the platforms serving all this curated output to us? Their profit motive is all wrapped up in getting us to click links, share stories, and scroll infinite feeds until we’re hypnotized — and when the software is encouraged to optimize some values to the exclusion of others, those others tend to take on extreme values.

Ve Haf Vays of Making you Tock

The police interrogation technique called “good cop/bad cop”? It works by exhausting our ability to compensate emotionally, literally outrunning the physiology that replaces neurotransmitters and flushes stress hormones from the body. Officers alternatively frighten and cajole, threaten and console, until the subject’s resistance just melts away. The technique makes us stupid and confused, unable to suppress our urge to blab something incriminating, and making us unable to understand the risk we’re in.

Now scroll your social media feed for a while. Boobs! Armageddon! Kittens! Climate change! Charity! War! A … I don’t know what that is, but here’s a quiz that only geniuses can score 100% on, in case you were feeling too good about yourself.

It’s good cop/bad cop running at 15 cycles per minute. I don’t know about you, but I have found myself scrolling five or six times in a row without realizing that I had failed to understand anything on the screen. Maybe the next thing will be good. Maybe the next thing will be good….. Eventually, something will piss me off enough to break through the brain fog.

So when we do get information that’s high-valence and that we should pay attention to — either to reject it as “fake news” or endorse it as useful — we’re not always in the best place, psychologically, to assess its actual merit. And so we tend to fall back on cognitive shortcuts like mere familiarity or confirmation bias as our guides. This is nothing new, of course, except that it’s now the fallacy equivalent of the Six-Million-Dollar Man, super-powered and superhumanly fast. Alas, reviewing what you already know is no way to learn new information or assess whether or not what you already know deserves amendment.

Too, we become desensitized by repeated or prolonged exposure, so in order to keep our eyeballs pointed at those profitable advertisements, the algorithms that choose what links and buttons should be available to us to click and share must offer up increasingly stimulating content — which is to say that what we’re fed tends to go to extremes.

Robot Overlords

Remember those black-box AI’s that nobody understands? Experts consider one of the most pressing problems in computer science (and ethics) to be what they’re calling “the control problem.” That is, how do we predict and constrain the behavior of systems that, almost by definition, we can never understand?

Let’s be clear, lest anyone take this out of context, because I’ll say far more arousing things below for you to be worried about: We’ve already seen that the AI we’ve assigned to curate that fraction of reality that we allow ourselves to be shown cannot be understood, but I’m not claiming that the program that populates your news feed is self-aware or has goals. (Yet.)

It is nevertheless a problem. One thing that should jump out at you when you begin to study the issue is the difficulty of optimizing multiple variables simultaneously. We want our social media feeds to amuse, inform, and connect us; Platforms want them to addict, control, and commoditize us. “‘Don’t make the mistake of thinking you’re Facebook’s customer, you’re not – you’re the product,’ [digital security expert Bruce] Schneier said. ‘Its customers are the advertisers.’”

So there are conflicting imperatives. But when one is preferred above the others, as time-on-site is strongly preferred by people trying to sell eyeballs to advertisers, other factors tend to go all wacky:

A system that is optimizing a function of n variables, where the objective depends on a subset of size k<n, will often set the remaining unconstrained variables to extreme values; if one of those unconstrained variables is actually something we care about, the solution found may be highly undesirable. This is essentially the old story of the genie in the lamp, or the sorcerer’s apprentice, or King Midas: you get exactly what you ask for, not what you want. A highly capable decision maker – especially one connected through the Internet to all the world’s information and billions of screens and most of our infrastructure – can have an irreversible impact on humanity.

Stuart Russell, Professor of Computer Science

What goes to extremes when social media optimize for time on site? Well, disinformation, for one. “[D]isinformation has been shown to have a more potent influencing impact than truthful information when the two are presented side by side.” Fake news is therefore more enticing and more sharable than real news. This has proven to have a politically biased effect. (The Left are not immune to their shibboleths, of course.) Outrage is another: “[A]nger is the emotion that spreads fastest on social media.”

Bottom line, if being terrified, angry, isolated, depressed, addicted, hypnotized, and misinformed makes you view and click ads without upsetting you so much that you throw down your phone, aggregator platforms have little incentive to constrain those variables, and I think there are few left who would say they aren’t going to extreme values, demonstrably harming our mood, affect, and productivity.

Accordingly, the AI give us what we consume, not what we need.

Real News about Fake News

During the 2016 U.S. Presidential campaigns, secretive billionaires, political partisans, and national governments with covert agendas spent many millions engaging in “Bio-psycho-social profiling,” also known as “cognitive warfare,” deranging the election.

(I’m not trying to go off on a whole tangent here, so even if you think they didn’t, I’m asking you to grant the logical possibility that they could. If I’m on the wrong side of your politics, just know that I think my own side is vulnerable to the same effects, so you’re welcome to take these posits as hypothetical or concern some other politics that bother you if it gets you to the end of this too-long raving.)

And they did it largely by the use of “bots” (software tools that post to social media sites as if they were humans) and the promotion of advertising under deceptive identities. There is substantial evidence that these efforts were effective, with estimates ranging up to 126 million Americans reached by Russian propaganda on Facebook alone. And Americans responded: They shared propaganda and misleading or frankly made-up “news” stories in huge numbers, and many of them showed up in person to fictive events promoted by foreign intelligence.

In an election decided at the last minute by a small number of states by margins just outside the boundaries of automatic recount, where the decisive advantage, arguably, was only 77,000 votes out of 130 million cast, it is not crazy to imagine that all this propagandizing turned the result, especially since most of the attention seemed to be focused against one of the two candidates.

So I’m taking it as given that manipulation of such things as social media feeds can effect significant political consequences, even though the last Presidential was so overdetermined that one could say that any one of several factors may have been decisive.

The Next Evolution

The fake news that may have turned the Presidential consisted largely of tweets, facebook pushes, text and pictures and blogs and activist screeds, and occasionally video or audio edited deceptively or used out of context.

By the time of the next Presidential election in 2020, I predict that the software needed to produce photo-realistic, full-motion video depicting public figures saying things they never said, so convincingly that non-experts or even experts without special equipment will not be able to tell the difference between fake video and real video, will be widespread. Technology of the sort that used to cost major motion-picture studios hundreds of thousands of dollars per scene will soon be available to anyone with a webcam and a youtube account. “This system obviously will be abused.”

And this is far from the only technology that aids our bamboozlement.

All together now….

So what happens when it all comes together?

We’ve seen that we self-assort voluntarily into discourse communities that can’t talk to each other, that we do not — cannot — understand the systems that govern the means of information, that these may optimize for undesirable results that nobody wants, and that partisans and profiteers will exploit and abuse these factors to our probable disadvantage.

The political pendulum now swings so far and fast that it threatens to overturn the clock. It’s not clear to me which way it will tip, Left, Right, or just crazy. So far, we have been somewhat protected by the fact that the powerful are politically diverse — for every Soros, there’s a Koch, more or less. But there now exists technology that can skew our discourse and steer our politics at machine speed and without accountability and possibly contrary to human interest and beyond our control. Who gains the advantage — or whether we all lose it together — may come down largely to chance, as may the survival of our political system.

Accordingly, I believe that there emerges a novel threat to liberty that would have made George Orwell wet his pants.

Frogs in Water

But supposing that instead of there being a rough balance of power such that the whole system of many actors pushing and pulling on each other doesn’t tend in any particular direction, there were a concerted effort to skew the system systematically in a chosen direction, with all of the means of persuasion and control mentioned above in play — and surely more that we don’t know about.

I don’t want to tie this to any particular company or entity, because any of many could suffice, so let’s just say that there is some entity X who wants or tends to determine the outcome of the next election. This could be a social media site, a wealthy partisan, a content aggregator, a news agency, or even a coalition (accidental or deliberate) of diverse entities. All that matters is that X tends toward some political outcome and can exert some measure of control over whether and what you know about things.

This X has all the big data about you that it needs to psychoanalyze your preferences well enough to know what will “seduce” you before you’ve ever heard of it.

Surely we’d see through their manipulations; we’re smarter than that, right? Not without some effort. We all like to think that advertising doesn’t work on us. We’re wrong. Many decisions can be predicted by mere familiarity with the options.

Suppose X knows that you care so much about climate change that this issue is likely to be decisive when you choose how to vote and that you are likely to consume media about it when it is suggested on your feeds. (Doesn’t matter which way. You could think it’s 100% man-made or a Chinese hoax; we’re only thinking about changing whatever you think.)

X inserts into your feeds and suggestions news coverage quite like what you would ordinarily consume about climate change, but the first month increases the probability that this coverage will include specified adjectives by 5%. It used to be neutral; now it’s biased to include words like “uncertain,” or “natural.” And the second month, 10%, and the third 15%. Maybe faster or slower than that; the algorithms will figure out what persuades without being noticed.

Supposing this method is used on every issue you care about. And everyone you know. For years. And the ads are promoted to you in your favorite colors, at the times you’re most likely to read them, from the sources you have most likely found credible in the past and which are shared by members of your family. Only gradually does less-familiar reporting sneak in under the radar of your novelty detectors.

We’re frogs in water. It would gradually begin to seem to us that certain opinions were generally accepted. Before, we only saw coverage that said climate change was a hoax, then for two or three years it seemed like more and more experts were coming around. Well, now, everybody seems to be saying they’re finally convinced. We don’t want to be the last person who hasn’t come around yet. I mean, this stuff has finally been proven! We need to do something!

Slipping into Dictatorship

Again, the last Presidential election was decided by a small margin and arguably at the last minute. Manipulation of public sentiment would not have to be terribly effective to change electoral outcomes, and it wouldn’t have to turn many voters to succeed, so we need not imagine armies of zombified partisans brainwashed into thoughtless compliance to see why there is a problem — just a few percent of the public tending and trending slightly differently than they would in the unforced situation of truly balanced media. And given any success at all, the candidates elected could plausibly (however slightly, at first) tend to be those likelier than otherwise to be friendly to policies that would facilitate — or at least not punish — manipulations of the self-same kind.

And manipulation of voter motivation has already been proven to work. In 2010, Facebook did a little experiment. It presented one body of users with information about the election with links to information about how to vote. It presented another body with the same information but which also showed pictures of contacts of the users who had clicked the “I Voted” button on Facebook. The pictures appear to have turned out an additional 340,000 voters — more than enough to be decisive in a hardfought election, and quite worrisome if applied with any political bias.

And given that the needed “push” might be so small, there wouldn’t necessarily be anything in particular to notice. After all, politics swings and then swings back; it would plausibly take several election cycles to prove any systematic bias in the process.

And we don’t even need to imagine a shadowy cabal meeting in smoke-filled rooms deliberately plotting to impose a fore-ordained orthodoxy on the public mind by deliberate propaganda out of malice aforethought (though that may be one of the scariest alternatives); it could just be that certain memes or politics — by pure chance — happen to be popular at the moment the technological momentum hands long-term control to whoever happens to have influence at that time, like a random allele going to fixation by genetic drift alone.

We would still think we were informed, we would still believe we were making rational decisions and casting meaningful ballots. We would still seem to have a government that would still seem to be crafting policies. But in fact, nobody (or not large enough fractions of everybody) would know what they would have to know to make a different choice.

This is akin to what’s called “ideological capture” — and ideological capture is a highly effective means of achieving regulatory capture. Presented over the long term with an information diet that rendered certain ideas emotionally, cognitively, politically, and socially beyond the pale, we simply would or could no longer consider alternatives. Our worldview would now be consistent with only a subset of possible outcomes, and we wouldn’t know and wouldn’t be able to acquire the information it would take to break the spell — and wouldn’t believe it if we did. We would now proceed down a decision tree with many of its branches pruned away, and no way to recognize their absence. We would be trapped by a circumscribed ontology, and a lopsided epistemology.

We would have slipped into dictatorship without even noticing. It could already have happened. How would you know?

What to do

This is not the yellow journalism of our great-grandparents’ generation. It is literally weapons-grade disinformation that has been proven to be effective, and time is short. It is clear that we need a media literacy campaign on the scale of the Manhattan Project. It is equally clear that we’re not going to get it. Therefore each of us must take new responsibility for our contribution to the problem, since almost none of us can strike at its root.

We need to take ourselves more seriously. Random youtubers and podcasters now have the reach of major publishing houses — and so, in the aggregate, may ordinary users of social media. That gif you just shared? You didn’t know this but it got shared by a guy whose friend shared it, too. From there, the black-box AI detected its popularity and promoted it to a a few hundred people. You didn’t even know it pinged a thousand phones and changed ten minds. I mean, you just sent it ironically, as a joke. Surely nobody believed it, right?

We are all broadcasters, and therefore we have an ethical responsibility to consider not only the accuracy but the tendency of the information we share online.

This goes beyond fact-checking. It goes beyond breaking out of your bubble and seeking evidence to challenge your views. It goes beyond being superficially critical of the information that crosses your path. We need to practice radical skepticism even — especially — of the information that confirms us in our prior belief, because we can no longer assume that we encounter it innocently.

And we must support those who are trying to stem the tide of propaganda and disinformation, like Snopes and Politifact and many others.

And we must use our power as denizens of the digital world and political system to pressure our policy-makers to take seriously the possibility that our politics may become dangerously destabilized — or rendered permanently inflexible — by the manipulation of internet-facilitated propagation of misinformation and ill-intended influence.

For I believe that hope is not lost. These are just the growing pains of a maturing technology, but we need to recognize our power and own the consequences of its use.

Update 3-23-18

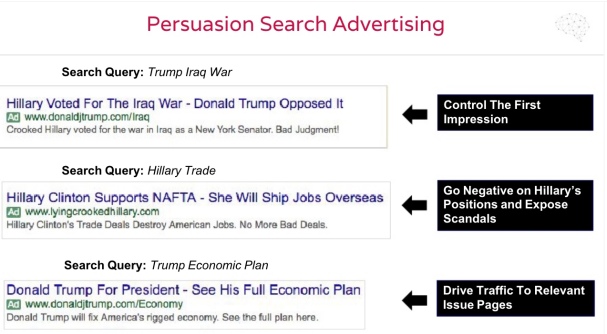

News continues to break about the use, abuse, and manipulation of social media, web searches, and the news to skew the result of the 2016 Presidential election in United States. Now supported by charts and graphs from within Cambridge Analytica, a company that stands accused of allegedly illegal possession of detailed data on 50 million users of Facebook, and which used this data to construct, redirect, and micro-target internet media content for the purpose of changing the electoral outcome.

Image: Scribd, Cambridge Analytica’s ‘Trump for President’ debrief.

It’s not theoretical. They are doing it.

Do you think these are the only ones? Do you think you’re immune?

Update 4-1-18

“This is extremely dangerous for our democracy.”

Local television is still one of the most popular way Americans get their news, which makes what Sinclair Broadcasting is doing seem all the more heinous. Local anchors at Sinclair stations across the country are forced to read propaganda from their corporate masters. In this case, propaganda that sounds like it was written in the White House press office. Deadspin has compiled a series of these of these right-wing rants that frighteningly show just how powerful this hype can be. As Dan Rather often says, the key to a strong democracy is a free and independent press. It’s sickening to watch local journalists who are forced to read something that trashes their own profession. Please note this is happening at nearly 200 television stations across the country.

Featured Image: Narrative Network of US Election 2012, Thinkbig-project, CC